Closer to the Edge: Hyperscaling Have I Been Pwned with Cloudflare Workers and Caching

I’ve spent more than a decade now writing about how to make Have I Been Pwned (HIBP) fast. Really fast. Fast to the extent that sometimes, it was even too fast:

The response from each search was coming back so quickly that the user wasn’t sure if it was legitimately checking subsequent addresses they entered or if there was a glitch.

Over the years, the service has evolved to use emerging new techniques to not just make things fast, but make them scale more under load, increase availability and sometimes, even drive down cost. For example, 8 years ago now I started rolling the most important services to Azure Functions, “serverless” code that was no longer bound by logical machines and would just scale out to whatever volume of requests was thrown at it. And just last year, I turned on Cloudflare cache reserve to ensure that all cachable objects remained cached, even under conditions where they previously would have been evicted.

And now, the pièce de résistance, the coolest performance thing we’ve done to date (and it is now “we”, thank you Stefán): just caching the whole lot at Cloudflare. Everything. Every search you do… almost. Let me explain, firstly by way of some background:

When you hit any of the services on HIBP, the first place the traffic goes from your browser is to one of Cloudflare’s 330 “edge nodes”:

As I sit here writing this on the Gold Coast on Australia’s most eastern seaboard, any request I make to HIBP hits that edge node on the far right of the Aussie continent which is just up the road in Brisbane. The capital city of our great state of Queensland is just a short jet ski away, about 80km as the crow flies. Before now, every single time I searched HIBP from home, my request bytes would travel up the wire to Brisbane and then take a giant 12,000km trip to Seattle where the Azure Function in the West US Azure data would query the database before sending the response 12,000km back west to Cloudflare’s edge node, then the final 80km down to my Surfers Paradise home. But what if it didn’t have to be that way? What if that data was already sitting on the Cloudflare edge node in Brisbane? And the one in Paris, and the one in well, I’m not even sure where all those blue dots are, but what if it was everywhere? Several awesome things would happen:

- You’d get your response much faster as we’ve just shaved off more than 99% of the distance the bytes need to travel.

- The availability would massively improve as there are far fewer nodes for the traffic to traverse through, plus when a response is cached, we’re no longer dependent on the Azure Function or underlying storage mechanism.

- We’d save on Azure Function execution costs, storage account hits and especially egress bandwidth (which is very expensive).

In short, pushing data and processing “closer to the edge” benefits both our customers and ourselves. But how do you do that for 5 billion unique email addresses? (Note: As of today, HIBP reports over 14 billion breached accounts, the number of unique email addresses is lower as on average, each breached address has appeared in multiple breaches.) To answer this question, let’s recap on how the data is queried:

- Via the front page of the website. This hits a “unified search” API which accepts an email address and uses Cloudflare’s Turnstile to prohibit automated requests not originating from the browser.

- Via the public API. This endpoint also takes an email address as input and then returns all breaches it appears in.

- Via the k-anonyity enterprise API. This endpoint is used by a handful of large subscribers such as Mozilla and 1Password. Instead of searching by email address, it implements k-anonymity and searches by hash prefix.

Let’s delve into that last point further because it’s the secret sauce to how this whole caching model works. In order to provide subscribers of this service with complete anonymity over the email addresses being searched for, the only data passed to the API is the first six characters of the SHA-1 hash of the full email address. If this sounds odd, read the blog post linked to in that last bullet point for full details. The important thing for now, though, is that it means there are a total of 16^6 different possible requests that can be made to the API, which is just over 16 million. Further, we can transform the first two use cases above into k-anonymity searches on the server side as it simply involved hashing the email address and taking those first six characters.

In summary, this means we can boil the entire searchable database of email addresses down to the following:

- AAAAAA

- AAAAAB

- AAAAAC

- …about 16 million other values…

- FFFFFD

- FFFFFE

- FFFFFF

That’s a large albeit finite list, and that’s what we’re now caching. So, here’s what a search via email address looks like:

- Address to search: [email protected]

- Full SHA-1 hash: 567159D622FFBB50B11B0EFD307BE358624A26EE

- Six char prefix: 567159

- API endpoint: https://[host]/[path]/567159

- If hash prefix is cached, retrieve result from there

- If hash prefix is not cached, query origin and save to cache

- Return result to client

K-anonymity searches obviously go straight to step four, skipping the first few steps as we already know the hash prefix. All of this happens in a Cloudflare worker, so it’s “code on the edge” creating hashes, checking cache then retrieving from the origin where necessary. That code also takes care of handling parameters that transform queries, for example, filtering by domain or truncating the response. It’s a beautiful, simple model that’s all self-contained within a worker and a very simple origin API. But there’s a catch – what happens when the data changes?

There are two events that can change cached data, one is simple and one is major:

- Someone opts out of public searchability and their email address needs to be removed. That’s easy, we just call an API at Cloudflare and flush a single hash prefix.

- A new data breach is loaded and there are changes to a large number of hash prefixes. In this scenario, we flush the entire cache and start populating it again from scratch.

The second point is kind of frustrating as we’ve built up this beautiful collection of data all sitting close to the consumer where it’s super fast to query, and then we nuke it all and go from scratch. The problem is it’s either that or we selectively purge what could be many millions of individual hash prefixes, which you can’t do:

For Zones on Enterprise plan, you may purge up to 500 URLs in one API call.

And:

Cache-Tag, host, and prefix purging each have a rate limit of 30,000 purge API calls in every 24 hour period.

We’re giving all this further thought, but it’s a non-trivial problem and a full cache flush is both easy and (near) instantaneous.

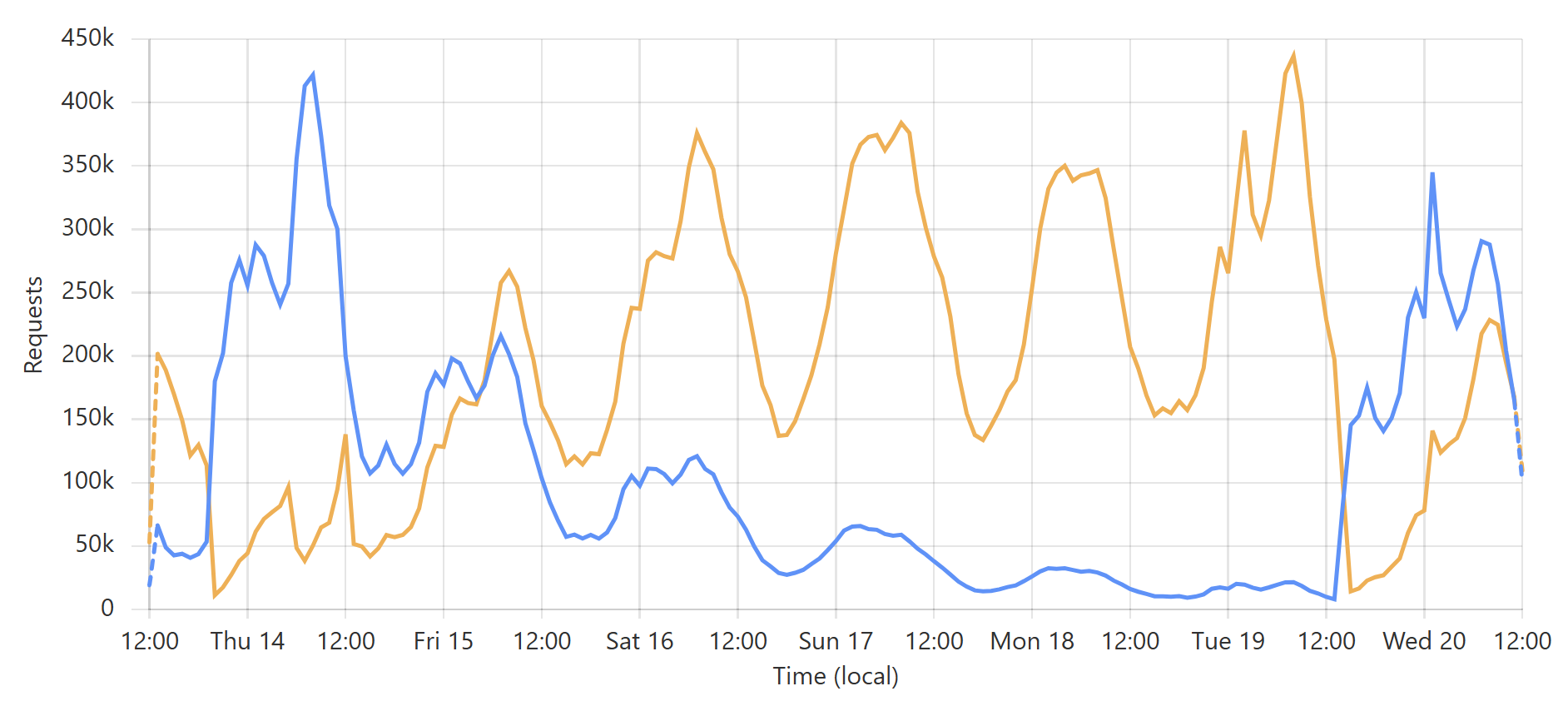

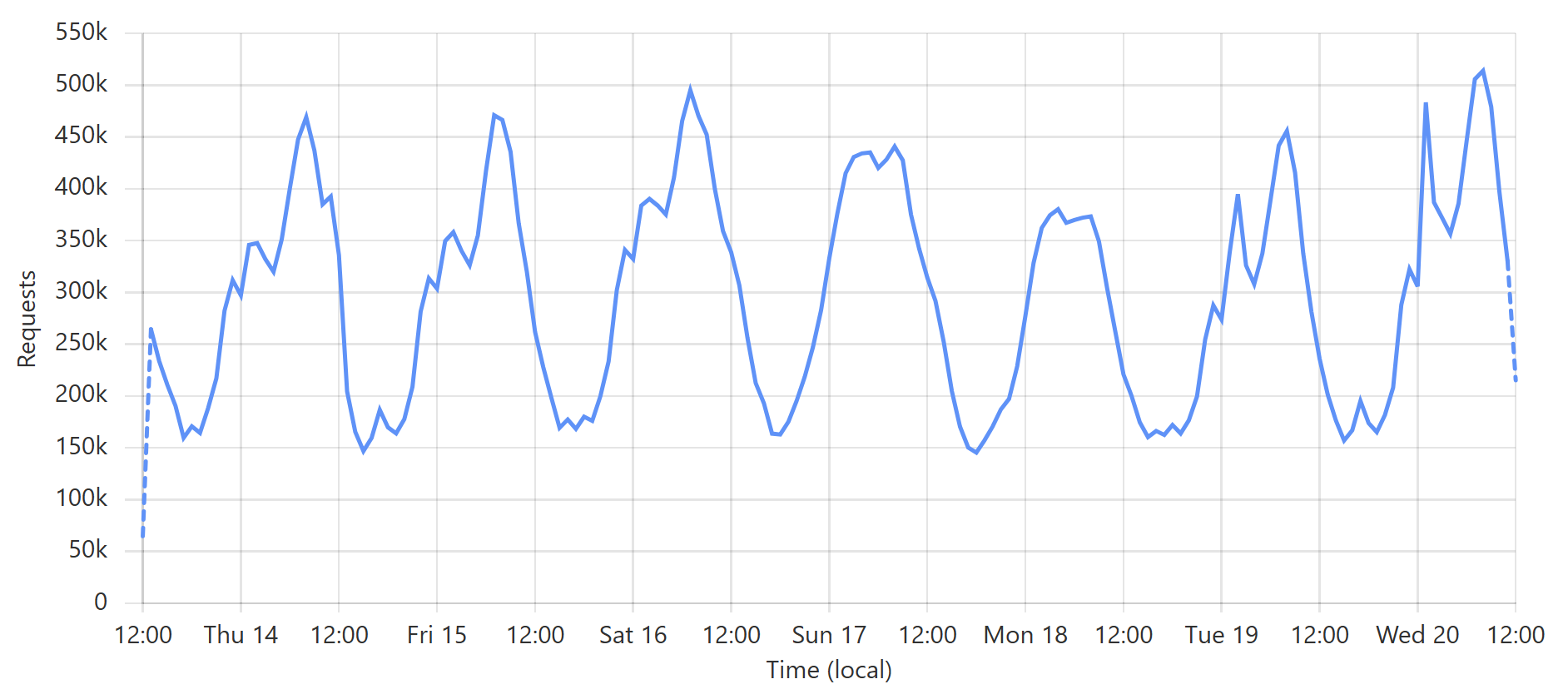

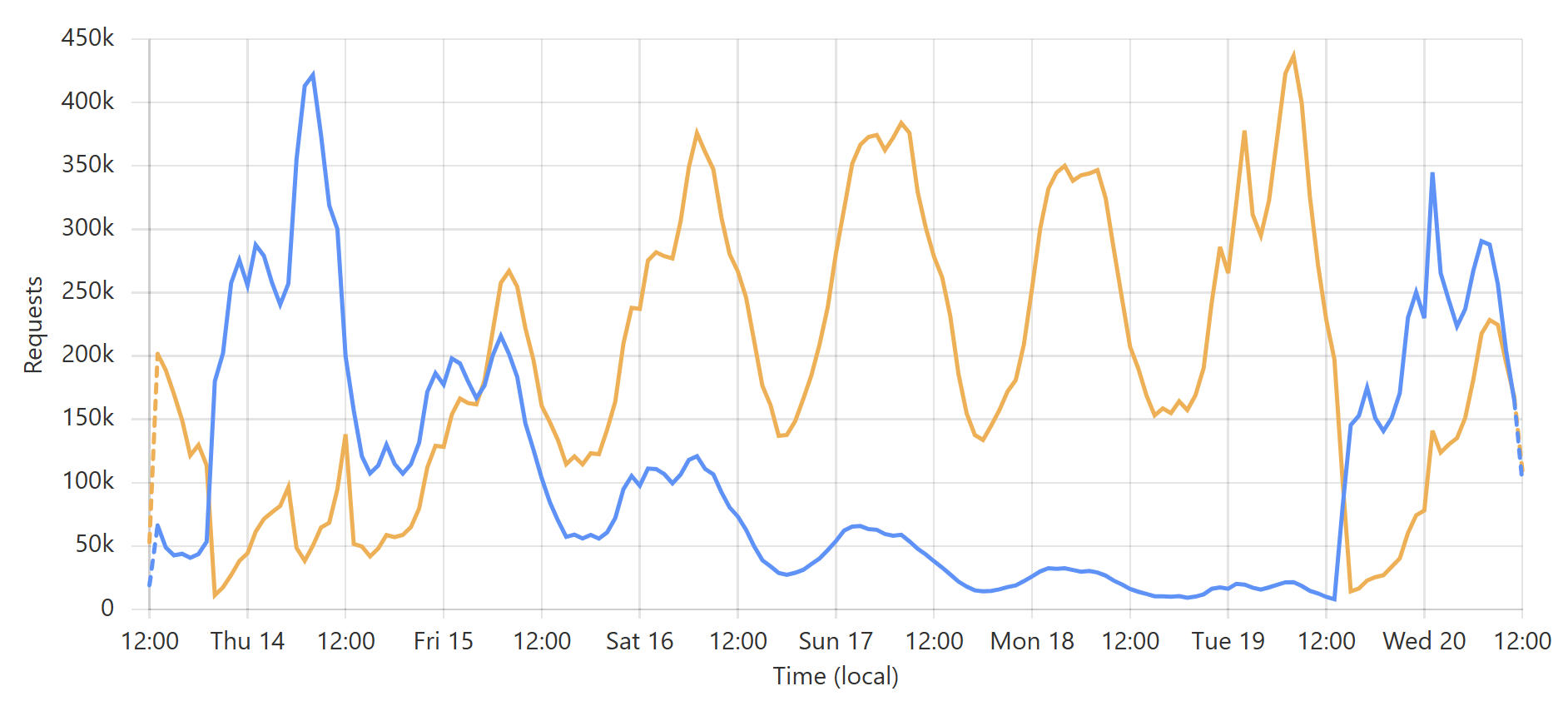

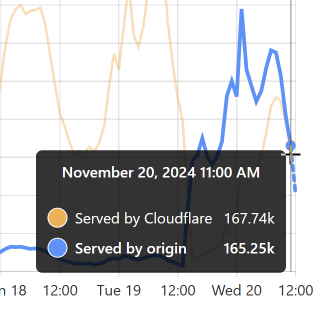

Enough words, let’s get to some pictures! Here’s a typical week of queries to the enterprise k-anonymity API:

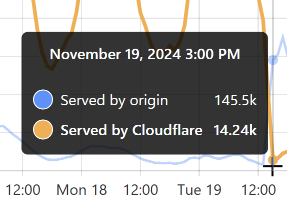

This is a very predictable pattern, largely due to one particular subscriber regularly querying their entire customer base each day. (Sidenote: most of our enterprise level subscribers use callbacks such that we push updates to them via webhook when a new breach impacts their customers.) That’s the total volume of inbound requests, but the really interesting bit is the requests that hit the origin (blue) versus those served directly by Cloudflare (orange):

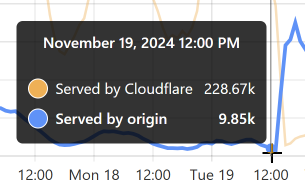

Let’s take the lowest blue data point towards the end of the graph as an example:

At that time, 96% of requests were served from Cloudflare’s edge. Awesome! But look at it only a little bit later:

That’s when I flushed cache for the Finsure breach, and 100% of traffic started being directed to the origin. (We’re still seeing 14.24k hits via Cloudflare as, inevitably, some requests in that 1-hour block were to the same hash range and were served from cache.) It then took a whole 20 hours for the cache to repopulate to the extent that the hit:miss ratio returned to about 50:50:

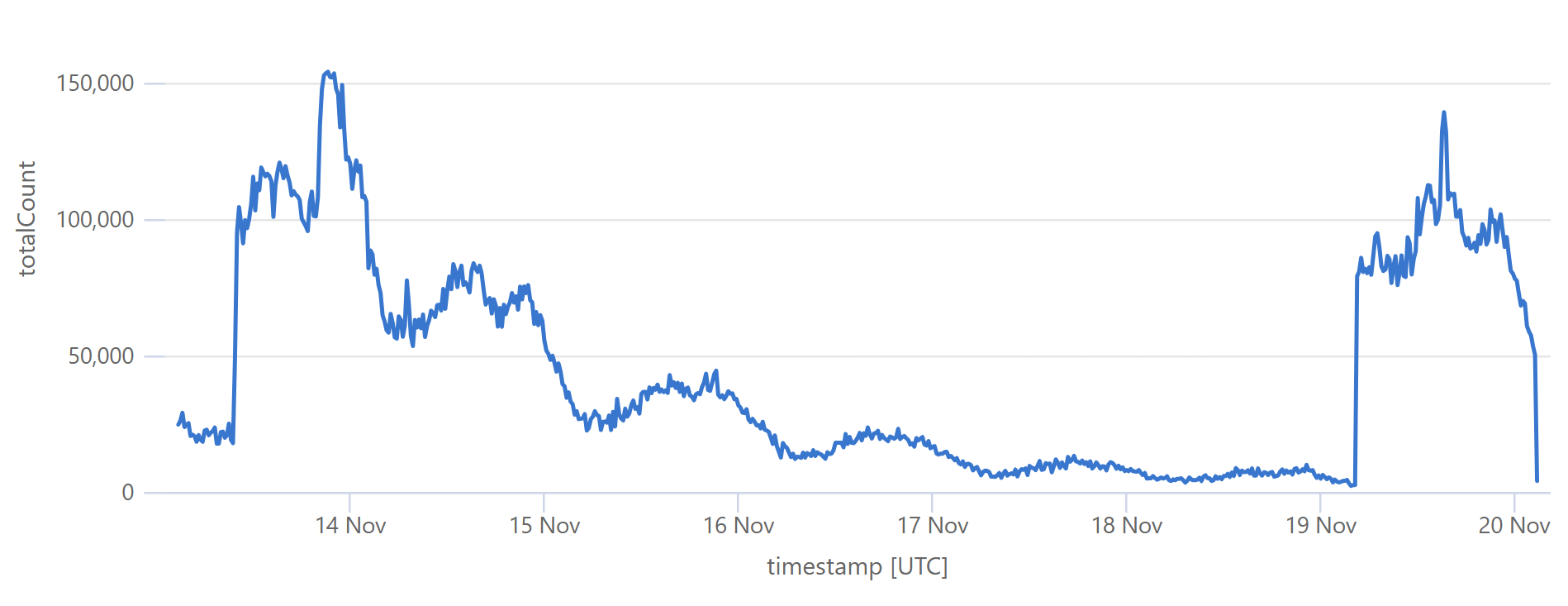

Look back towards the start of the graph and you can see the same pattern from when I loaded the DemandScience breach. This all does pretty funky things to our origin API:

That last sudden increase is more than a 30x traffic increase in an instant! If we hadn’t been careful about how we managed the origin infrastructure, we would have built a literal DDoS machine. Stefán will write later about how we manage the underlying database to ensure this doesn’t happen, but even still, whilst we’re dealing with the cyclical support patterns seen in that first graph above, I know that the best time to load a breach is later in the Aussie afternoon when the traffic is a third of what it is first thing in the morning. This helps smooth out the rate of requests to the origin such that by the time the traffic is ramping up, more of the content can be returned directly from Cloudflare. You can see that in the graphs above; that big peaky block towards the end of the last graph is pretty steady, even though the inbound traffic the first graph over the same period of time increases quite significantly. It’s like we’re trying to race the increasing inbound traffic by building ourselves up a bugger in cache.

Here’s another angle to this whole thing: now more than ever, loading a data breach costs us money. For example, by the end of the graphs above, we were cruising along at a 50% cache hit ratio, which meant we were only paying for half as many of the Azure Function executions, egress bandwidth, and underlying SQL database as we would have been otherwise. Flushing cache and suddenly sending all the traffic to the origin doubles our cost. Waiting until we’re back at 90% cache it ratio literally increases those costs 10x when we flush. If I were to be completely financially ruthless about it, I would need to either load fewer breaches or bulk them together such that a cache flush is only ejecting a small amount of data anyway, but clearly, that’s not what I’ve been doing 😄

There’s just one remaining fly in the ointment…

Of those three methods of querying email addresses, the first is a no-brainer: searches from the front page of the website hit a Cloudflare Worker where it validates the Turnstile token and returns a result. Easy. However, the second two models (the public and enterprise APIs) have the added burden of validating the API key against Azure API Management (APIM), and the only place that exists is in the West US origin service. What this means for those endpoints is that before we can return search results from a location that may be just a short jet ski ride away, we need to go all the way to the other side of the world to validate the key and ensure the request is within the rate limit. We do this in the lightest possible way with barely any data transiting the request to check the key, plus we do it in async with pulling the data back from the origin service if it isn’t already in cache. In other words, we’re as efficient as humanly possible, but we still cop a massive latency burden.

Doing API management at the origin is super frustrating, but there are really only two alternatives. The first is to distribute our APIM instance to other Azure data centres, and the problem with that is we need a Premium instance of the product. We presently run on a Basic instance, which means we’re talking about a 19x increase in price just to unlock that ability. But that’s just to go Premium; we then need at least one more instance somewhere else for this to make sense, which means we’re talking about a 28x increase. And every region we add amplifies that even further. It’s a financial non-starter.

The second option is for Cloudflare to build an API management product. This is the killer piece of this puzzle, as it would put all the checks and balances within the one edge node. It’s a suggestion I’ve put forward on many occasions now, and who knows, maybe it’s already in the works, but it’s a suggestion I make out of a love of what the company does and a desire to go all-in on having them control the flow of our traffic. I did get a suggestion this week about rolling what is effectively a “poor man’s API management” within workers, and it’s a really cool suggestion, but it gets hard when people change plans or when we want to apply quotas to APIs rather than rate limits. So c’mon Cloudflare, let’s make this happen!

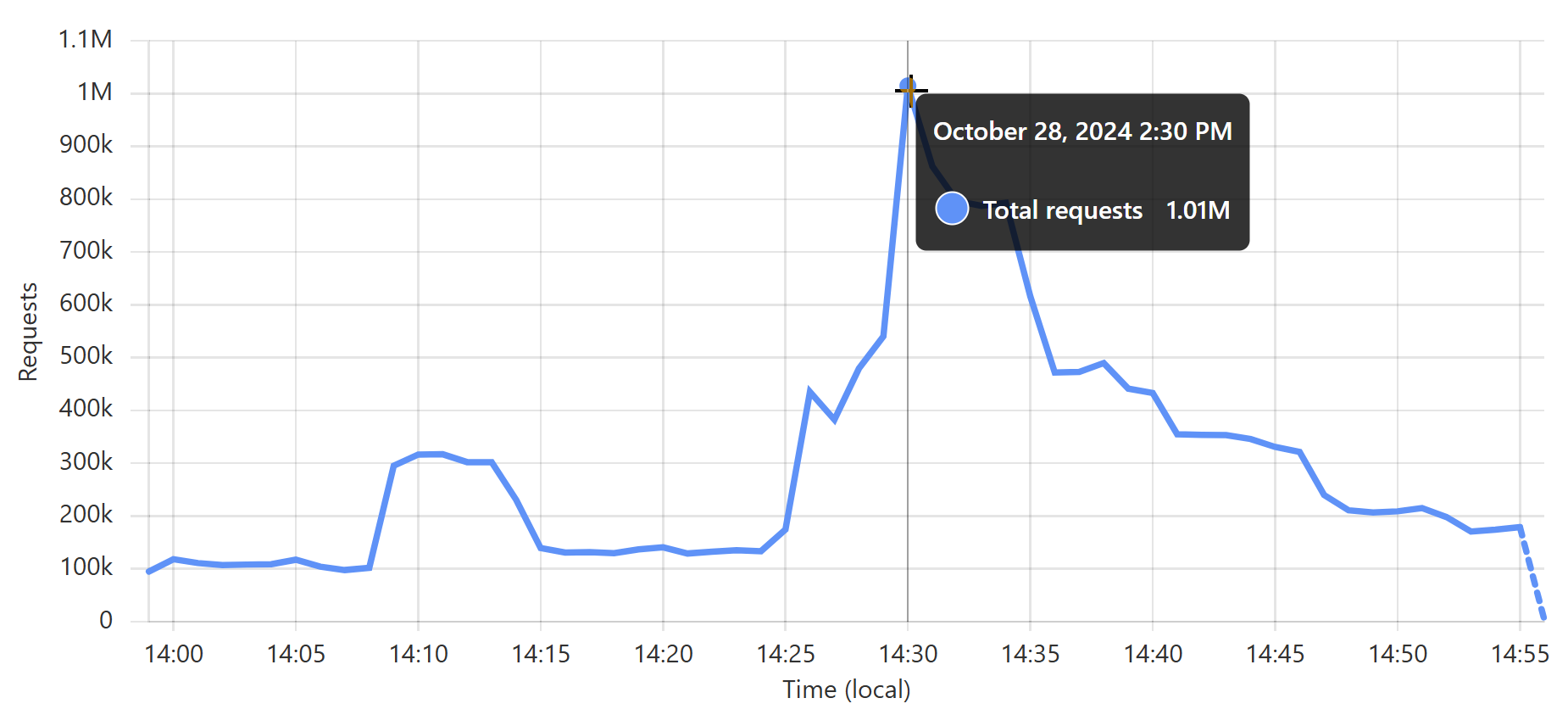

Finally, just one more stat on how powerful serving content directly from the edge is: I shared this stat last month for Pwned Passwords which serves well over 99% of requests from Cloudflare’s cache reserve:

There it is – we’ve now passed 10,000,000,000 requests to Pwned Password in 30 days 😮 This is made possible with @Cloudflare’s support, massively edge caching the data to make it super fast and highly available for everyone. pic.twitter.com/kw3C9gsHmB

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) October 5, 2024

That’s about 3,900 requests per second, on average, non-stop for 30 days. It’s obviously way more than that at peak; just a quick glance through the last month and it looks like about 17k requests per second in a one-minute period a few weeks ago:

But it doesn’t matter how high it is, because I never even think about it. I set up the worker, I turned on cache reserve, and that’s it 😎

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post, Stefán and I will be doing a live stream on this topic at 06:00 AEST Friday morning for this week’s regular video update, and it’ll be available for replay immediately after. It’s also embedded here for convenience:

Troy Hunt

Go to troyhunt